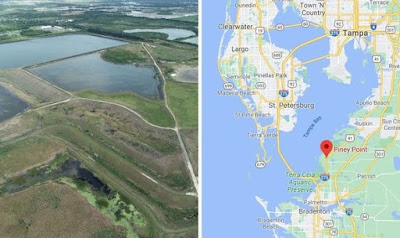

A leak at an old phosphate plant site has threatened Tampa Bay for the last week with environmental catastrophe. Here we break down the pieces involved.

It used to be a fertilizer manufacturing facility. Industrial byproducts of that process are still stored on site. That includes polluted water and phosphogypsum, a substance kept in stacks and monitored for its radioactivity. Managing those materials is expensive and hasn’t always gone well at Piney Point. Past discharges have hit the valuable waters of Bishop Harbor. Excess nutrients from wastewater can feed harmful algal blooms, which lead to fish kills.

What’s a phosphogypsum stack?

Drive through Central Florida and you might see one. They rise like large, flat-topped hills above an otherwise level state.

Phosphogypsum is a leftover from processing phosphate, which is part of making fertilizer.

The Environmental Protection Agency has a webpage all about it, noting that “phosphate rock mining is the fifth-largest mining industry in the United States in terms of the amount of material mined.”

It’s a big business in Florida, a hub for fertilizer production. One of Tampa’s biggest companies is Mosaic, a miner.

Phosphate rock, according to federal regulators, contains phosphorus and also uranium and radium. Phosphorus is what fertilizer manufacturers want. They dissolve the rock “in an acidic solution” and that leaves phosphogypsum. Think of a slurry that dries out, creating what the government refers to as “a crust, which blocks most of the radon.”

“Most of the naturally-occurring uranium, thorium, and radium found in phosphate rock ends up in this waste,” the Environmental Protection Agency says. “Uranium and thorium decay to radium and radium decay to radon, a radioactive gas. Because the wastes are concentrated, phosphogypsum is more radioactive than the original phosphate rock.”

Where does water come in?

Ponds of wastewater are sometimes stored atop phosphogypsum stacks. They may hold rainwater, as well as what’s known as process water — left by fertilizer production. Process water is acidic and carries nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. The Florida Industrial and Phosphate Research Institute explains that if a plant shuts down, that water has to “be treated before it can be discharged.” In 1997, a wastewater overflow at Piney Point’s sister plant in Polk County sparked a devastating fish kill in the Alafia River.

It’s a mix of seawater from an old dredging project that Piney Point’s operator — with the support of public officials — agreed to take on about a decade ago, putting more water on the site; rainwater; and remnant process water from the fertilizer operation.

Estimates suggest there were 480 million gallons of wastewater in the reservoir when the leak began. It is unclear how much could be drained or if the reservoir will collapse before the current incident ends.

County officials have said they are hopeful that even if the reservoir that is leaking bursts completely, other ponds on the site might not follow in the collapse. But they said some of those ponds might have more contamination, whereas the reservoir at the center of the current incident has had fish living in it.

Are there any power plant wastewater ponds nearby?

My first reaction when I heard this story is that I thought it was from a power plant. Here is a map of map of power plants in Florida. Thankfully no as you can see by this map below.